Investing in Women and Children During World War II

On June 29, 1943, the U.S. Senate passed the first (and only) national childcare program (the Lanham Act) to provide for children whose mothers were employed for the duration of World War II. It was justified by lawmakers as necessary in supporting mothers to enter the workforce in support of war production. By the end of the war, day care centers were created in 386 communities, and over 6 million women worked to support war efforts. By July 1944, 3,102 childcare centers existed in all but New Mexico and Washington DC, and included 130,000 enrolled children. Between 550,000 and 600,000 children are estimated to have received some care from government supported programs during this time. Unfortunately, the programs investing in women and children were discontinued after the war.

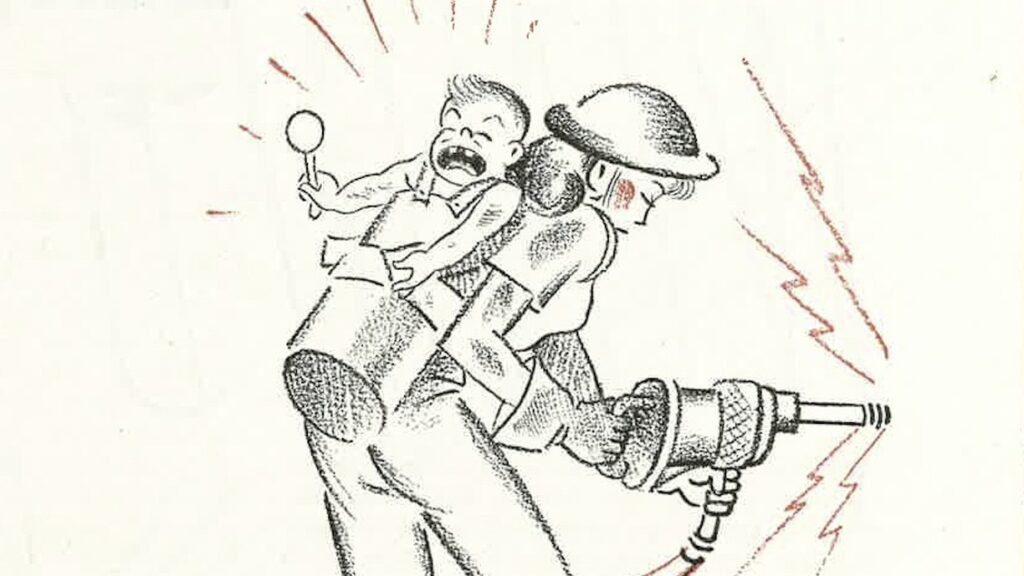

An image of Rosie the Riveter that appeared in a 1943 issue of the AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION magazine

Many consider the Lanham programs to be of historical importance. It was the first time in American history when parents of any social status or income could send their children to federally-subsidized child care, and to do so affordably. Because these centers served families across the socioeconomic spectrum, the public became more familiar and comfortable with the idea of sending young children away from the home for part of the day. This is important because the arrangement addressed the needs of families, specifically, women and children. The centers were found to have a strong and persistent positive effect on the well-being of children.

In fact, a 2016 study following children from birth through age 35 found that high-quality care during the earliest years benefits children for generations to come. Other studies show children participating in high-quality care grow up to earn more, acquire better jobs, have improved health, more education, and decreased criminal activity than their peers who did not receive quality care as a young child.

Women in the Workforce Today

Fast forward to 2019. 64 percent of women with children under the age of six are in the workforce. The average annual cost to send an infant to daycare can exceed a year’s tuition and fees at a public university. High childcare costs pressure women to drop out of the workforce because, in many cases, the price of childcare would surpass earnings from a job. In addition, the lack of affordable child care contributes to the long-term earnings gap between men and women.

And now, in 2021, the world is reeling from the COVID pandemic. Women in the U.S. have lost 5.3 million jobs during the pandemic. 2.3 million women (compared to 1.8 million men) have left the workforce because of things like layoffs or lack of childcare (closure of centers). Additionally, 42% of women with children under the age of 2 have left the workforce during the pandemic. Women’s labor force participation is at a 33-year low.

In 2021, 1 in 4 child care providers remains closed, and 166,800 fewer people are working in that industry than a year earlier. Not only does this impact mothers, but also the impact is amplified for the 92% of women (43% of those are women of color) who work in the early learning and care industry.

We’ve been depending on an invisible care infrastructure upheld by women, particularly women of color, and without it, everything collapses. This is the biggest opportunity in generations to reset our systems and policies. C. Nicole Mason of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research is excited about the opportunity because the low wage workers who used to be invisible to us are now called “essential” during the pandemic.

The United States historically has put far less investment into early learning and care than other developed countries, making access for families inconsistent and costly. Profit margins are such that providers cannot pay livable wages. For example, a provider who accepts a 4-year old from a family paying with a child care subsidy can expect to receive an average of only $3.60 per hour from the state to care for and educate that child. This lack of profit for the provider leaves many childcare workers (92% are women, around half are mothers of children under 18, and 40% are women of color) struggling to afford childcare themselves.

Additionally, inconsistent policies within the system leaves professionals providing early learning and care for children in a disjointed, undervalued field. Educators find it difficult to navigate preparation, responsibilities, expectations, and compensation levels. Even if they manage to progress through the system, they often find themselves earning the same wages, with the same work responsibilities (and more), as they had earlier in their careers. In addition, depending on the state or the agency for which educators work, the compensation can look drastically different for doing the same job.

Same Job, Different Pay

All of these educators have a bachelor’s degree. But even with the same education qualifications, their pay still varies depending on the setting in which they work:

| Infant/Toddler Teacher | $27,248 |

| Head Start Teacher | $33,072 |

| Community-Based Public Pre-K | $33, 696 |

| Public School Pre-K Teacher | $42,848 |

| Public School K-12 Teacher | $56,130 |

Investing in Women and Children During the Pandemic

New policies and programs during the pandemic, such as the CARES Act, are a much appreciated bandaid for a broken system. However, funds and policies related to these changes are most likely temporary. Critics want to see more permanent changes, such as child care infrastructure, paid sick leave for caregivers, a higher minimum wage, and economic impact payments, to name a few. Experts are hopeful, as President Biden and Education Secretary, Miguel Cardona, have proposed an aggressive platform (for both families and providers) related to early learning and care.

The changes and support of early learning and care by the U.S. government during the pandemic are born out of crisis, and address weaknesses, as well as highlighting examples of how we can strengthen an essential service American families rely on to nurture and educate their children while they participate in the economy.

Programs offered during crises, such as the Lanham Act during WWII and the CARES Act during the 2020 pandemic, temporarily support the early learning and care system. Through these crises, we see what can happen when childcare is viewed as a collective responsibility. We have a great opportunity to reset our systems and policies and invest in women and children.

Comment and make it public on Facebook